I was at my mum’s house the other day when she returned home from Asda with her weekly shop. Being the slightly odd son she’s grown to accept, I proceeded to interrogate her.

“Mum, how much conscious effort do you think you put into selecting the items you bought today?” I asked.

Rather than validating my question with a verbal response, I was met with a blank, almost disinterested look I’ve seen before.

Undeterred, I interrogated further, keen to know if she felt that at any point she had really thought about any of the items she placed in her trolley.

Equally undeterred, she continued to look at me like a commuter does a bus timetable, yet interestingly when I looked through the bags she had everything she needed and wanted, rather than a completely random collection of useless items.

This brief exchange didn't reveal anything out of the ordinary, it pretty much reflects how we all shop, all the time.

In fact, 95% of purchase decisions are made without conscious thought (Gerald Zaltman, 2003… an actual professor at Harvard).

This means for every 20 purchases we make, we only pay conscious thought to one of them. What’s more, it means we engage our conscious brain to consider precisely none of the products we purchase in an average supermarket trip (where we purchase 19 items).

This shouldn’t come as a surprise to any of us. It’s not new news.

Daniel Kahneman may have only coined the terms ‘System 1’ and ‘System 2’ in 2011 (to define the different modes of thinking), but he and Amos Tversky were studying dual-process theory back in the 1970s. And 80 years before that, back in the 19th century, William James was describing two ‘different types of thinking’ identified as "habit" and "reasoning”.

In short, it’s a very very long time since we discovered that we humans are anything but rational, and just as long since it became known (if not accepted) that any attempt to build a brand by appealing to the rational mind is nothing more than a fools errand, and any belief that humans frequently make rational, considered, and ultimately correct decisions is wrong. No offence.

Without getting into a detailed history of the evolution of the human brain, it is important for marketers to know the basic mechanics that cannot be changed, to better appreciate the consequences for brands.

The reason we don’t think consciously about even a small fraction of the things we purchase is the same reason we can drive a car whilst having a conversation without crashing (most of the time), why we can listen to a podcast when walking without falling over or get dressed in the morning without having to think too hard about where our pants and socks go.

It’s all because of a single survival mechanism baked into each and every one of us… We are programmed to save the conscious, deliberate and effortful attention (or ‘System 2’ mode of thinking) for when we really need it (like spotting a Lion before it eats one of our kids – something that might have saved my mum a lot of stress) by pushing as much cognitive load as possible onto the unconscious, automatic, immediate (‘System 1’) mode of thinking.

Imagine spending a full 8-hour working day constantly focused on solving extremely complicated mathematical equations. You’d be mentally drained and physically tired, you’d be unable to focus attention on anything else throughout that time and far less likely to spot any potential risks or threats (it’s a good job mathematicians’ children are rarely left unattended near lions).

This doesn’t just mean that being remembered is important for a brand to succeed, it means it is the single most important factor in a brand’s success.

So, if the bad news for marketers is that people don’t simply engage conscious thought to rationally assess one product vs the available alternatives before making a rational, considered purchase decision.

The good news is that the brands that do manage to establish a place in the automatic, unconscious mind of their audience (which controls 95% of their decisions), will enjoy success far greater than the sum of their relative rational benefits.

Possibly the most obvious example of this anywhere in the world is Coca-Cola: the world’s largest soft drink brand, which enjoys a consistently massive market share advantage over Pepsi, the omnipresent challenger.

But in 2004, the most comprehensive blind study of Coke vs Pepsi ever (by Lichtenstein, Hsee & Bazerman) involved drinking Cola while strapped into an MRI machine. It found there was no meaningful difference in the pleasure experienced when tasting either product, thus proving beyond any subjective doubt that there is no physical product advantage.

Even more interestingly, the only difference in brain activity (and in the enjoyment of the product) became apparent when people were told which brand they were drinking. If they were told it was Coca-Cola, they didn’t just enjoy the drink more, their brains also showed more positive taste-related pleasure… even if they were actually drinking Pepsi.

And obviously this isn’t just the preserve of the world’s most famous brand. Whilst it would be a stretch to say that any unforgettable brand will be strong enough to alter brain activity during consumption, we can say with confidence that when meaningful product advantages aren’t huge, the brands that come to mind quicker and stay there longer will be selected over those that don’t.

Yorkshire Tea selling more teabags than any other brand in the UK has more to do with how quickly it comes to mind, and the positive associations linked to it (think Kaiser Chiefs, Patrick Stewart and ‘proper tea’), than the specifics of their tea blends and sustainability credentials.

Cadbury’s Gorilla, Pantone 2685 C and decades of that ‘glass and a half full of joy’ have sold more bars of chocolate than any physical product difference between their chocolate and any other like Galaxy or Nestle.

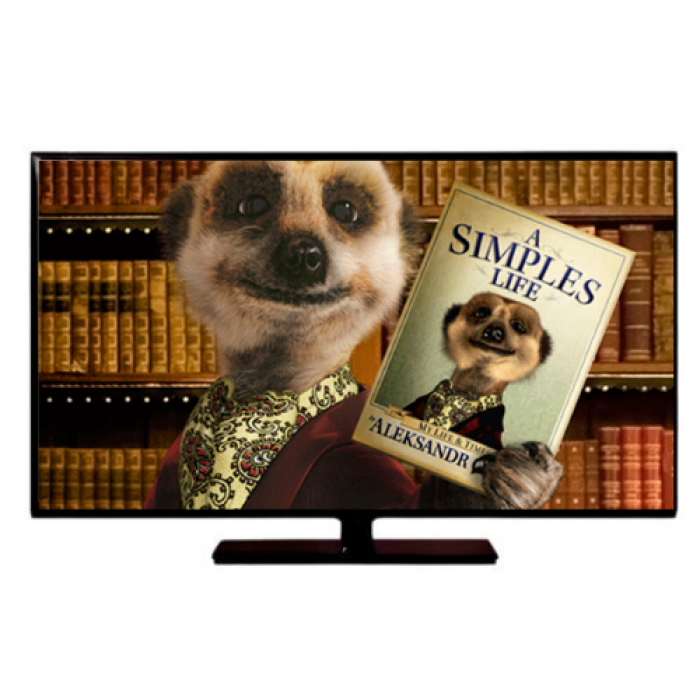

Compare the Market, Warburton’s, Lurpak, McCain, Budweiser, Fairy… the same is true of most great consumer brands.All these brands are nothing without their products, but owe everything to that tiny space they hold in the automatic, unconscious mind, which they’ve taken and hold because of an irrational approach to brand communications that penetrates deeper into the mind than the alternatives.

They’ve become unforgettable.